Explore the Science of Aging

Exploiting Biochemical Pathways to Extend Healthspan

The Science of aging

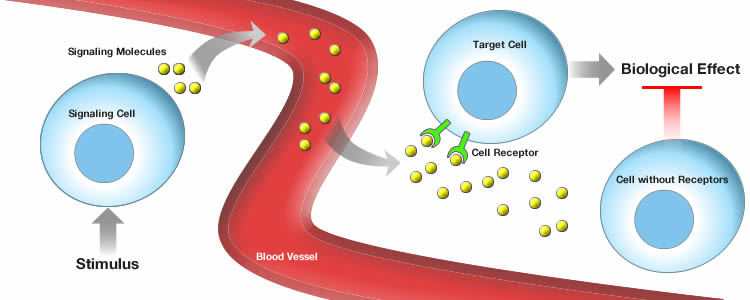

The primary characteristic of aging is the progressive loss of physiological integrity which ultimately leads to impaired function of cellular processes and increases the vulnerability to various human pathologies. Cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disorders and neurodegenerative disorders are manifestations of these human pathologies.

Over the past few years, aging research has been experiencing unprecedented advancements. In particular, reports from recent research indicate that aging is controlled by biochemical processes and to some extent by genetic pathways conserved in evolution.

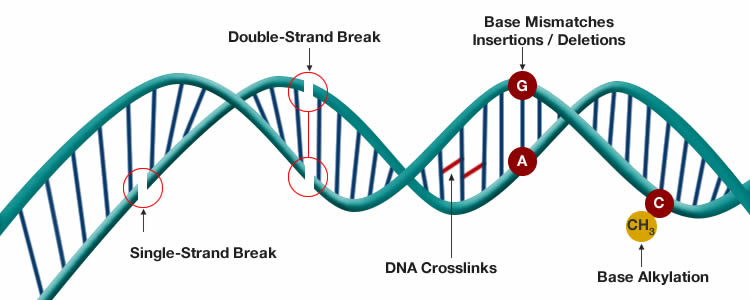

Genomic instability

Over time exposure to harsh environmental conditions can cause damage to our genome (DNA). This is further exacerbated by errors in DNA replication and stresses applied to the system. Although there are mechanisms in place to counter these effects, the accumulation of damage to the genome over the course of a lifetime can cause mutations which can eventually lead to cancer formation.

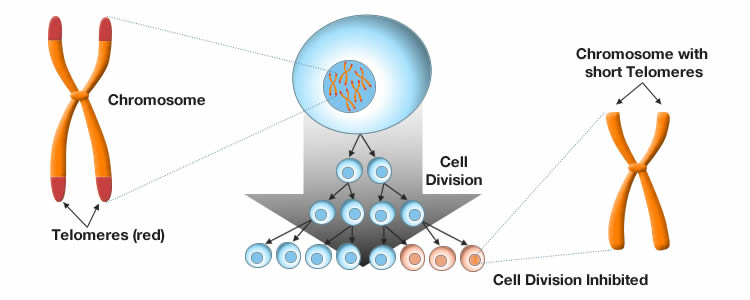

Telomere attrition

Telemores are structural elements found at the end of each DNA strand that help protect the DNA from deterioration. They act as caps at the terminal ends of the chromosomes insulating them from the environment. However, during each cycle of DNA replication and cell division, the telomeres are not fully replicated and become shorter over time. The loss of telomere length eventually leads to a point where DNA replication is no longer viable and cell growth is arrested thereby limiting the ability of tissues to regenerate.

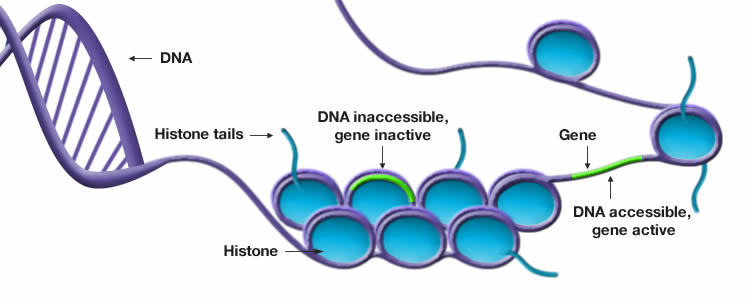

Epigenetic alterations

DNA holds all the instructions for generating various functional proteins, tissues and organs. The epigenetic code is a control layer on top of the DNA that influences how genes are read. In more simpler terms, the epigenetic code acts as a switch informing the cell which genes should be expressed (turned on) or suppressed (turned off) at a specific time and location. This interplay between the genome (DNA) and the epigenome results in the synthesis of cell, tissue or organ differentiation. For example, if a cell should develop into a heart cell, the epigenome will ensure that the parts of the genome specific to heart cells are expressed, while the parts specific to other cell types are ignored. However, the epigenetic code is not impervious to errors and over time undergoes change. Modifications to the epigenetic code often leads to irregularities in gene expression and cellular behavior ultimately causing our bodies to be vulnerable to disease.

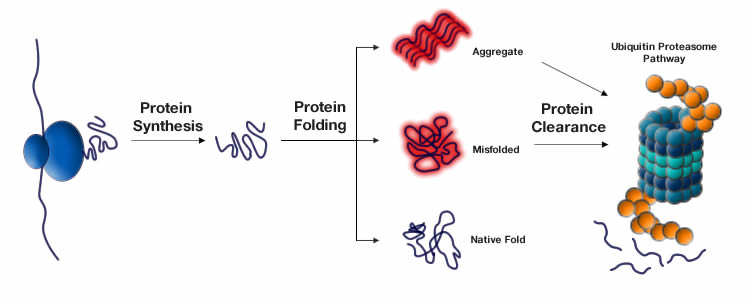

Loss of proteostasis

Proteins are the machines that build and drive our bodies. In each of our cells, proteins are constantly being synthesized and degraded through a process known as proteostasis or protein homeostasis. The correct and balanced biogenesis, folding, trafficking and degradation of proteins present within and outside the cell play a critical role in successful development, healthy aging, and resistance to environmental stresses. Any destabilization in the mechanisms of proteostasis results in an accumulation of improperly shaped proteins leading to dysfunctional components, celluar toxicity and in some cases to cancer.

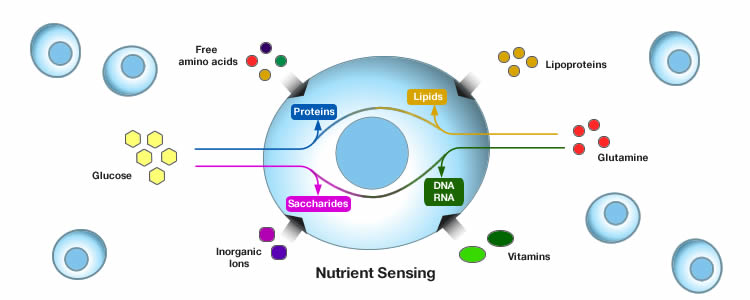

Deregulated nutrient sensing

Depending on the availability or scarcity of food our bodies respond differently. During times of nutrient abundance, cells and tissues activate nutrient sensing pathways to engage anabolism and store energy. In times of food scarcity, cellular repair mechanisms such homeostasis and autophagy are triggered. When our bodies are continuously exposed to food availability, the nutrient sensing mechanisms become desensitized eventually leading to metabolic disorders such as obesity and diabetes. Deregulation of the nutrient sensing pathways also occurs during aging as over time cells become unresponsive and fail to normally regulate energy production, cell growth, and other crucial cell functions.

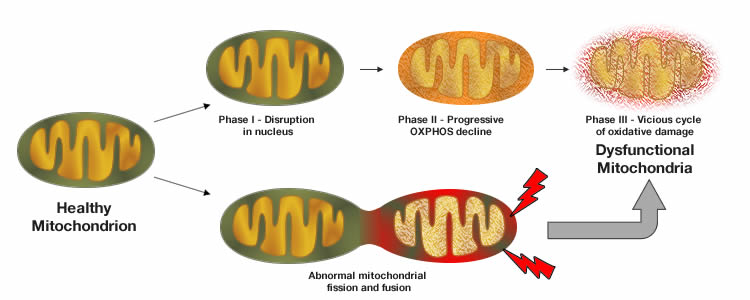

Mitochondrial dysfunction

Most of the energy a cell expends is produced in the mitochondria in the form of ATP, adenosine triphosphate. Mitochondria are therefore considered the powerhouse of the cell. The regulation of productive mitochondria is essential to cellular viability. Productive and healthy mitochondria are controlled through mitophagy, which is the selective degradation of defective mitochondria following damage or stress by autophagy. As our bodies age, the level of mitophagy markedly declines causing an increase in free radicals or otherwise known as reactive oxygen species (ROS) which in turn gives rise to the number of dysfunctional mitochondria. This suggests that a decline in mitophagy and the presence of dysfunctional mitochondria might induce the vicious circle of oxidative stress-induced, age-related cellular damage.

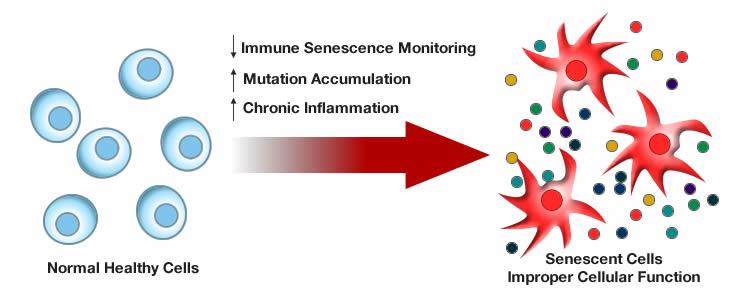

Cellular senescence

When a certain amount of DNA damage or stress is inflicted on cells, they enter a state of stable growth arrest and cease to divide. This phenomenon is called cellular senescence and it is a protective mechanism that prevents damaged cells from becoming cancerous. However, the presence of of an abundant number of senescent cells prevents the replenishment of cells and tissues. Although senescent cells do not divide, there presence is disruptive in that they also change behavior and secrete pro-inflammatory molecules that damage cellular environments and may contribute to chronic inflammatory diseases.

Stem cell exhaustion

Injuries that our bodies incur over our lives are remedied or repaired by stem cells. However, as we age the reservoir of stem cells is depleted and their ability to replenish damaged tissues declines. As with normal somatic cells, stem cells are also subject to many of the environmental stresses, such as DNA damage as well as epigenetic modifications which deteriorate their function. Over time this results in stem cell exhaustion.

Explore the Scientific knowledge-base of Aging

Innovative Nutraceuticals.

Guided by Science.